The hitchhiker’s guide to improving rural transport

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

On the road again.

If you happen to be reading this on Sunday morning, I shall be hitchhiking across the middle of the Istrian peninsula in Croatia: from the pretty coastal town of Rovinj to the administrative centre, Pazin, and onward to Rijeka – the city from which I am booked to fly to London on Sunday afternoon.

The first bus of the day is at 4.40am. Too early for me. The next is at 12noon, which would not get me to the airport early enough. So I shall, once again, place my travel fortunes in the hands of strangers.

So far this week, hitchhiking has worked out well. I have not been thumbing for the sake of it, but purely to fill gaps in public transport: either where there is none at all, particularly close to international frontiers, or where there are hours to wait between buses.

For example, I paid a prodigious amount to Swiss Federal Railways for a ticket to the northernmost railway station in Switzerland (Schaffhausen) and onwards by bus to the village of Bargen. But as often happens, public transport expires short of frontiers – in this case with Germany. Franz helped out.

Later that same day, en route to the source of the Danube, I faced a 90-minute wait for a bus, which was eliminated courtesy of Sergei. From the Danube to the Rhine, where Karina picked me up after travelling on the international free ferry that connects Germany with France.

Organised ridesharing was less successful. A week ago I arrived in Milan to discover a rail strike was in progress. I wanted to reach the Swiss border at Chiasso and duly put in a request at BlaBlaCar, the pan-European rideshare company. Several possible drivers popped up – but each of them, in turn, said, “Actually I’m not making that journey now,” except for the last, who simply didn’t respond.

Yet locally organised ridesharing is the best hope for rural transport for the future. After Labour took power, I posted my recommendations for the most pressing issues on social media. Sort out the rail disputes, of course; tax aviation in line with environmental harm; and, I added: “Road pricing is essential.”

The response was fast and mainly furious. One of the more polite ripostes was from Paul Saxton, who wrote: “Road pricing will hit people in rural areas where there is no alternative to using your car, as public transport is non-existent.”

Pushing up tax for rural motorists could be one effect of an unsophisticated road-pricing scheme – but a smarter version would aim to nudge urban, suburban and intercity drivers onto public transport. If buses are non-existent, people in those areas should not be punished financially for “involuntary car ownership”, as it is known. Rural bus services are mostly poor.

There are, though, other ways to make car ownership non-essential besides pouring yet more millions into running often-empty buses. One is demand-responsive transport – dial-a-ride as it was originally known, before technology improved to the point where, in northeast England, a system called Tees Flex runs a fleet of minibuses linking Darlington, Hartlepool and Middlesbrough with nearby locations.

The French, though, are way ahead. An organisation called Rezo Pouce, based in the southwest, aims “to make hitchhiking a mode of transport like any other, so that everyone can move when they want, where they want”.

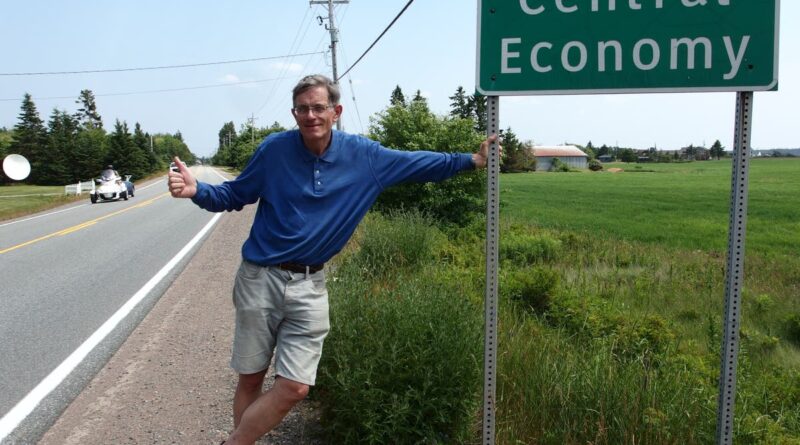

I have no great safety concerns about thumbing across Istria. Decades of hitchhiking have proved almost entirely danger-free. But I understand that hitching is not for everyone. Indeed, these days it seems that standing by the side of the road with an outstretched thumb is the sole preserve of the guide-book fraternity, notably Tony Wheeler (Lonely Planet co-founder), Hilary Bradt (Bradt Guides) and me (Europe: A Manual for Hitch-hikers).

Technology can be harnessed in rural areas so that locals travel with their neighbours. The village of Seix, for example, has a signpost where carless residents can converge and get lifts with their vehicle-driving fellow citizens. Rezo Pouce says that nine out of 10 journeys involve a wait of less than 10 minutes, which is frankly a better run rate than I can manage.

One part of the world where I hope the concept will be tested is the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. For reasons that elude me, it has been the place where my hitchhiking dreams go to die. Perhaps next time I could sign up as a verified, non-threatening candidate for transportation. Meanwhile, Croatia is mid-table in the ease-of-thumbing table, and I hope my journey proves smooth as well as surprising – you never know who you will meet on the road.